Race for the rails: How billion dollar logistics war is unlocking Africa’s hinterland

This shift from tarmac to track is driven by the need to slash transit times, reduce carbon emissions by 75%, and unlock the continent’s economic potential for the green energy transition.

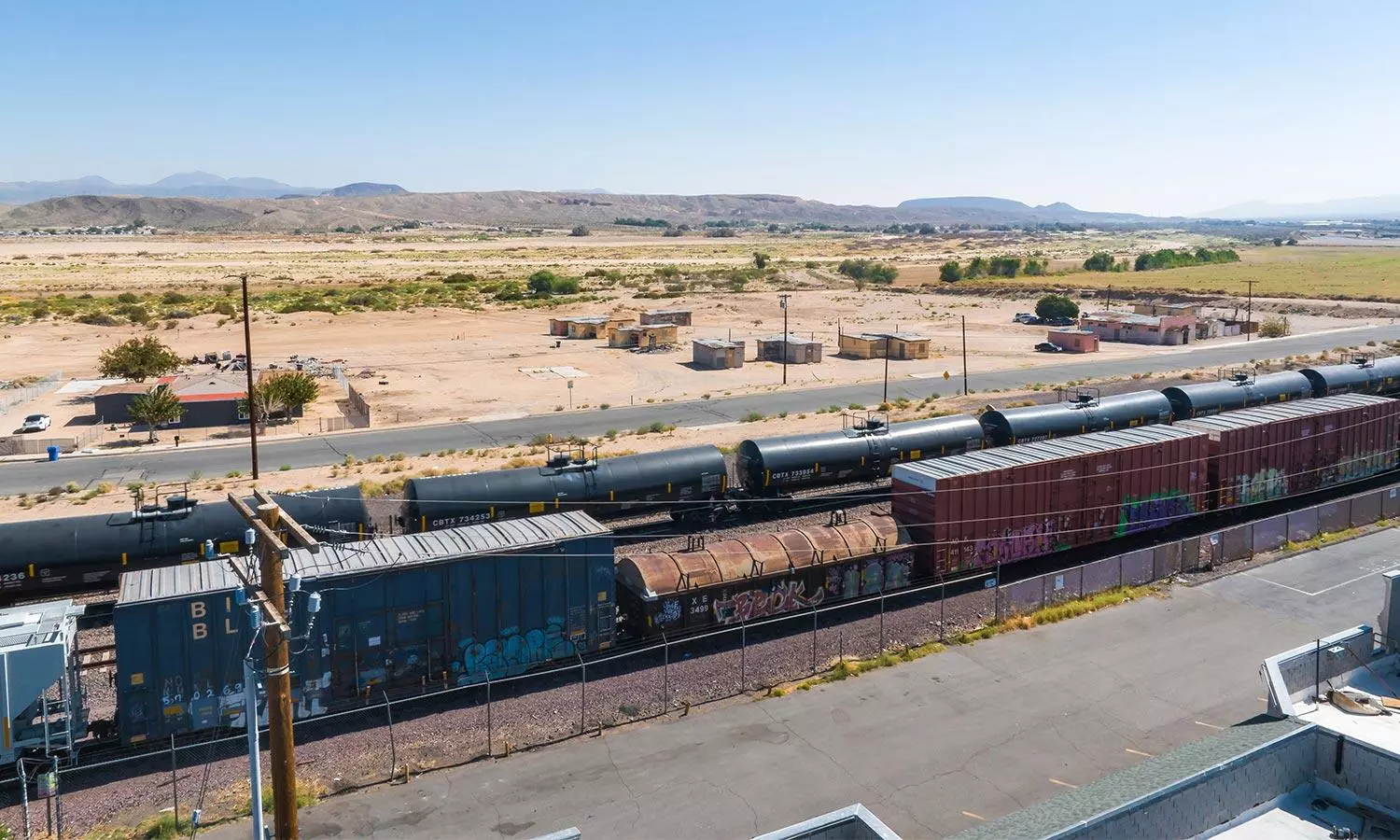

Currently, 80% of African freight moves by road, in the mineral-rich Copperbelt, this statistic is not just a number; it is a stranglehold. A single heavy-duty truck carrying 30 tonnes of copper does as much damage to the tarmac as 10,000 passenger cars. The trucks destroy the roads they depend on, slowing transit times to a crawl, spiking maintenance costs, and choking the continent’s economic potential.

Driven by a global scramble for critical minerals and the internal pressure of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), a new logistics paradigm is emerging. From the Atlantic coast of Angola to the Indian Ocean shores of Tanzania, a multi-billion dollar ‘Race for the Rails’ is underway.

Africa Race for the Rails refers to the intense geopolitical and economic competition, particularly in Southern Africa, as global powers (US, China, EU, Japan) race to develop and control critical railway corridors to secure access to the continent's vast reserves of minerals essential for the green energy transition, with major projects like the Lobito Corridor and the Tazara Railway at the center of this strategic scramble for supply chains.

To understand why the shift to rail is inevitable, one must first count the cost of the road.

For the miners in the DRC, who supply 70% of the world’s cobalt, the road reliance is a massive risk. Exporting via Durban involves a 3,000km odyssey through frequent bottlenecks, border extortion, and hijacking hotspots. The transit time can exceed 30 days. In an era of volatile commodity prices, having a month’s worth of inventory stuck on a truck is a balance sheet disaster.

Rail freight is not only cheaper over long distances; it is singular in its efficiency. One train can remove 100 trucks from the road, slashing carbon emissions by 75% and bypassing the chaotic border posts entirely.

According to the Roadmap for the freight logistic system in South Africa report, “The inability to export goods via rail is the most severe constraint on economic growth after the electricity supply shortfall, and requires urgent intervention”.

The western challenger: The Lobito Corridor

The first shot in the new railway war was fired not by a mining company, but by the White House and Brussels.

The Lobito Corridor is the flagship project of the G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII). It is a direct challenge to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, designed to link the mineral heart of the DRC to the Angolan port of Lobito on the Atlantic coast.

The logistics of the Lobito route are compelling. By heading West instead of South or East, shippers can cut the transit time from mine to ocean to under 10 days. For cargoes bound for the US or Europe, the Atlantic port shaves another week off the maritime journey compared to sailing from Dar es Salaam or Durban.

"The trip used to take 45 days to get to the United States... Now it takes less than 45 hours [by rail to the port. It's a game changer. It's faster, it's cleaner, it's cheaper, and most importantly, it's just plain common sense," said Amos Hochstein, U.S. Senior Advisor for Energy and Investment.

The Lobito Atlantic Railway (LAR) consortium is a partnership between commodities giant Trafigura, construction firm Mota-Engil, and operator Vecturis, has secured a 30-year concession. The US and EU have committed over $1 billion in loans and grants to upgrade the 1,300km line.

"This isn't just about moving rocks," says a US diplomat in Lusaka. "It’s about integrating the Angolan and Congolese economies. It’s about creating an agricultural corridor where farmers can finally get their goods to market without them rotting on a truck."

The proof of concept is already here. In August 2024, the first shipment of copper from the DRC reached the US via this route, a milestone that signaled the corridor is open for business.

The eastern incumbent: TAZARA’s rebirth

If the West is betting on the Atlantic, China is doubling down on the Indian Ocean.

In the 1970s, Mao Zedong built the TAZARA railway (Tanzania-Zambia Railway Authority) as a gift to the liberation movements of Southern Africa. It was an engineering marvel, winding 1,860km through the Rift Valley to the port of Dar es Salaam. By 2023, annual freight volumes had collapsed to less than 500,000 tons.

Beijing has returned to fix what it built. China has pledged $1 billion to refurbish the line. This isn't just a patch-up job; it is a complete modernisation aimed at restoring TAZARA’s capacity to handle millions of tons of cargo annually.

For Chinese mining giants in the DRC, TAZARA is the strategic lifeline. It offers a direct route to Chinese smelters via the Indian Ocean. The revitalisation will involve not just track repairs, but a complete overhaul of the signaling systems and the introduction of modern rolling stock that can handle heavier axle loads.

The green ledger

The Road-to-Rail shift is also being forced by the boardroom ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) mandate.

For decades, the decision to move copper by road or rail in Central Africa was a simple calculation of price and speed. But in 2026, a new variable has entered the equation, one that is proving just as powerful as the profit margin: the Carbon Ledger.

As global mining giants race to decarbonise, the Road-to-Rail shift has morphed from a logistical convenience into an existential necessity. With investors in London and New York scrutinising Scope 3 emissions (the indirect pollution generated by a company’s supply chain), the convoy of diesel-belching trucks navigating the potholed roads of the Copperbelt has become a liability that balance sheets can no longer hide.

Barrick Gold, operating the Lumwana mine in Zambia, faces similar pressure. The company has publicly committed to reducing its Scope 3 emissions by 30% by 2030.

Since Barrick cannot control the emissions of the Chinese smelters that buy its concentrate, its most effective lever for reduction is logistics. The expansion of the Lumwana Super Pit is heavily predicated on the availability of a rail solution to lower the carbon intensity per ounce of copper produced.

"Lumwana is on course to join the world’s list of large and strategically important copper mines... becoming a flagship for sustainable copper mining. We’re not just expanding a mine; we’re laying the foundation for lasting economic and social development that will endure long after mining ends," said Mark Bristow, at the Lumwana Super Pit expansion launch in July 2025.

Institutional investors are increasingly unwilling to fund projects that rely on high-emission trucking fleets when lower-carbon alternatives exist. As the EU implements its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), copper entering Europe with a high transport carbon footprint could soon face penalties.