Foreign imports, factory closures reshape South Africa’s auto industry

Once considered an anchor of industrial employment, the sector now faces its sharpest disruption in decades.

Source: Pexels

South Africa’s automotive sector is in transition. The sound of machinery in some factories has gone silent, replaced by uncertainty over trade barriers, import competition, and eroding local output. Once considered an anchor of industrial employment, the sector now faces its sharpest disruption in decades.

According to a CNBC Africa report published on August 13, 2025, figures released by Trade Minister Parks Tau in August revealed the depth of the problem. Twelve companies have closed operations within two years, and more than 4,000 workers have lost their jobs. Domestic sales have slowed, with 515,850 locally produced vehicles sold last year, far below the target set under the South African Automotive Masterplan 2035. Imports now account for 64% of all cars sold in the country. Localisation, the measure of local input in production, stands at 39%, well short of the government’s 60% target.

The country’s industrial framework was designed around major global players — Volkswagen, Toyota, and Mercedes-Benz — which have dominated South Africa’s assembly lines for decades. But the current phase is shaped by new external forces. Chinese brands such as Chery are flooding dealership floors with competitively priced products. Global manufacturers like Stellantis are planning to localise in regions such as the Eastern Cape, but the pace of investment has not yet balanced the impact of foreign imports already saturating the market.

The decline in local production is not confined to smaller component suppliers. Ford Motor Company of Southern Africa announced late in August 2025 that it would lay off more than 470 employees across its Silverton assembly plant in Pretoria and its Struandale engine plant in Gqeberha. The company stated that these steps were necessary to adjust production capacity amid slowing regional demand and changing export conditions. Solidarity, the labour union representing workers, confirmed the figures and warned of potential follow-on layoffs across the supplier chain. Willie Venter, the union’s deputy general secretary, called the decision a “warning to the entire industry”.

The closures and layoffs come against a backdrop of evolving global trade politics. The imposition of 30% tariffs by the United States, announced by President Donald Trump earlier this year, has restricted access to South Africa’s R28.7 billion automotive export market. Washington and Pretoria remain locked in talks over a revised trade framework that could reduce the duties, but analysts expect the negotiations to take months. The tariffs have forced local carmakers to reroute shipments and reprice exports, undermining profits and threatening long-standing supply contracts.

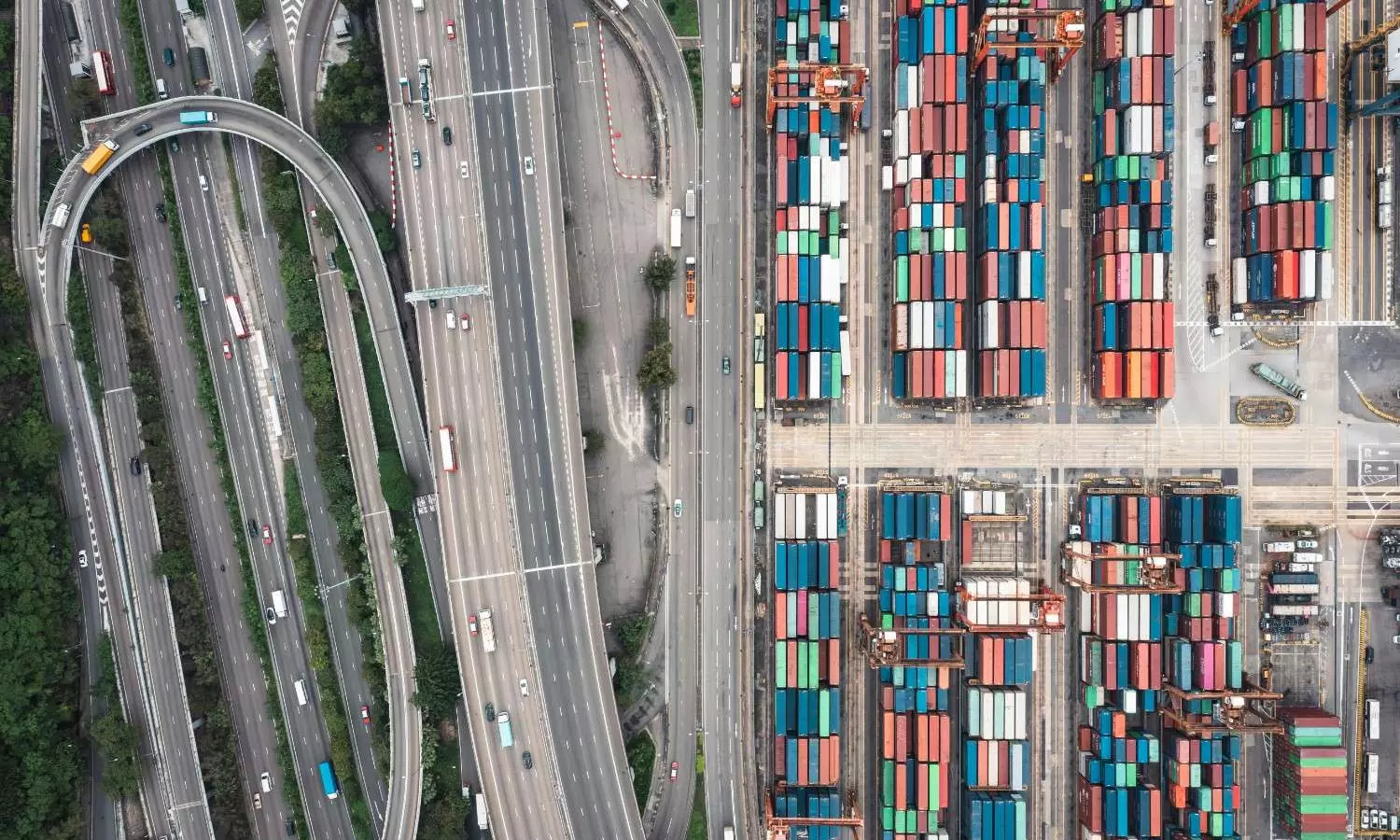

While domestic producers struggle, inbound shipments continue at scale. Durban’s port, one of the busiest automotive terminals in Africa, has seen a steady stream of vessels unloading imported vehicles. Industry analysts say importers benefit from favourable logistics and production incentives abroad that South African makers cannot easily match. The market’s appetite for affordable and technologically advanced cars — particularly hybrid and electric models — has also grown. Many of these vehicles come preassembled from Asia or Europe, bypassing local manufacturing entirely.

Volkswagen South Africa continues to operate in Kariega, but its global parent company faces scrutiny over supply chain practices. Investigations by Deutsche Welle have linked its European manufacturing network to African mineral smelters accused of fuelling conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Although Volkswagen stated it does not maintain direct business relationships with those entities, the findings have renewed discussions about ethical sourcing within the wider automotive ecosystem. The controversy highlights another layer of complexity for a sector where corporate accountability and local development increasingly intersect.

For South Africa, the concentration of imports poses structural risks beyond employment. Local content stagnation has reduced secondary demand for steel, plastics, and industrial services. According to Minister Tau, a modest five-percentage-point rise in local manufacturing content could generate up to 30 billion rand in new procurement, roughly seven times the country’s current auto export value to the United States. Yet without incentives that favour local production and infrastructure investments to lower costs, meeting that potential remains difficult.

CNBC Africa noted that automotive manufacturing employs roughly 115,000 people directly, including around 80,000 in component production. Those jobs represent a significant share of the nation’s industrial workforce. The closures of assembly and parts factories ripple through logistics firms, mining suppliers, and regional economies built around vehicle plants. The government’s revised manufacturing support plan now includes electric vehicles and related components in an effort to attract new entrants and stabilise the sector.

The shift from domestic assembly to import reliance reflects more than a cyclical downturn. It marks a turning point in South Africa’s relationship with the global car industry. As long as trade barriers remain high, localisation lags, and low-cost imports dominate the market, the country’s automotive sector will continue to shrink. Reversing that trend will depend on whether new investment, improved trade terms, and manufacturing reforms can restore the industry’s capacity to compete.